Visiting the Birthplace of Sen no Rikyū:The Aesthetics of Wabi Tea and Tosogu

- gallery陽々youyou

- Feb 1

- 5 min read

The aesthetic sensibility that finds beauty in irregular and distorted forms in works of Higo kinko was deeply influenced by the culture of wabi-cha inherited by Hosokawa Sansai, one of Sen no Rikyū’s renowned Seven Disciples. The tea ceremony was regarded as an essential form of cultural refinement and stood as a symbol of the spirit of the time.

From this perspective, it is natural to develop an interest in visiting the place where Sōeki—later known as Rikyū—first encountered Zen and the Way of Tea, and in exploring his hometown. This led to a journey to Sakai in Osaka, with an extended visit to Kitano Tenmangū in Kyoto. In this article, the aesthetics of Sen no Rikyū are examined through sites associated with him, beginning in Sakai, Osaka.

Sen no Rikyū

Sen no Rikyū was born in Sakai in Daiei 2 (1522) into a prominent merchant family, bearing the

childhood name Tanaka Yoshirō. He passed away at the age of sixty-nine on April, 21st in Tenshō 19 (1591).

The great master of wabi-cha adopted the Buddhist name Sōeki and took the art name Hōsensai, derived from Zen terminology. In his later years, he was granted the title Rikyū Koji by Emperor Ōgimachi. From an early age, Rikyū began Zen training at Nanshū-ji Temple in Sakai. By the age of seventeen, he had already begun studying tea under Kitamuki Dōchin, and later entered the circle of Takeno Jōo, who further deepened the spirit of wabi-cha initiated by Murata Jukō during the Muromachi period.

It is well known that Rikyū gained the trust of both Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi, serving them as chadō (tea master) and contributing to the organization of numerous tea gatherings. However, the fact that Rikyū’s tea—profoundly infused with Zen philosophy—also influenced sword fittings may be less widely recognized.

Rikyū’s Zen and the Way of Tea: Ryūkōzan Nanshū-ji

Nanshū-ji Temple is said to have originated in Daiei 6 (1526), when Kogaku Sōkan, then abbot of Daitoku-ji in Kyoto, renamed a small temple in Sakai as Nanshū-an. Later, in Kōji 3 (1557), Miyoshi Nagayoshi relocated the temple to pray for the repose of his father Motonaga’s soul, founding Nanshū-ji with Dairin Sōtō as its founding abbot.

The city of Sakai flourished under the Miyoshi clan, and it is an interesting coincidence that Nagayoshi and Rikyū were of the same age. The sangai-bishi combined with kuginuki (nail-puller) motif was the mon of the Miyoshi family and frequently appears in Muromachi-period sukashi tsuba. It may have been a design honoring Nagayoshi, regarded as the first supreme ruler of the Sengoku period. The graves of the Miyoshi clan are located within the grounds of Nanshū-ji.

Murata Jukō studied Zen under Ikkyū Sōjun at Daitoku-ji, and both Takeno Jōō and Sen no Rikyū trained at Nanshū-ji. Rikyū is said to have taught, “The technique comes from Jōo; the Way derives from Jukō,” suggesting that the spirit of “chazen ichimi”—the unity of tea and Zen—was established here.

Within the temple complex are the tea room Jissō-an, favored by Rikyū, and a water basin transmitted from Kōsen-ji that Rikyū cherished. Jissō-an features a nijiriguchi entrance, requiring all who enter—regardless of status—to bow, kneel, and crawl inside after leaving their swords outside. This act symbolically separates one from worldly rank and enters an egalitarian space.

The location outside the nijiriguchi where swords were set down is considered the origin of the okishiki-katanagake, a freestanding sword rack used in tea rooms.

Sakai Taian and Muichian

At Sakai Rishō no Mori in Osaka, there are reconstructed interpretations of Taian, the National Treasure tea room, known as Sakai Taian, as well as Muichian. Muichian is said to be the four-and-a-half mat (tatami) tea room built by Rikyū for the Kitano Grand Tea Ceremony, held by Toyotomi Hideyoshi at Kitano Tenmangū on October 10th, Tenshō 15 (1587).

Detailed measurements of this tea room are recorded in texts such as the Hosokawa Sansai Chasho, indicating the close relationship between Sansai and Rikyū.

When visiting Kitano Tenmangū in Kyoto, I noticed the Hoshi-ume (Star Plum) mon, which is said to have been used exclusively by Rikyū. The plum blossom is deeply associated with Sugawara no Michizane, the enshrined deity of Kitano Tenmangū, and has long been revered as a tree of special spiritual significance.It is possible that Rikyū’s use of the Hoshi-ume mon was connected to the Kitano Grand Tea Ceremony.

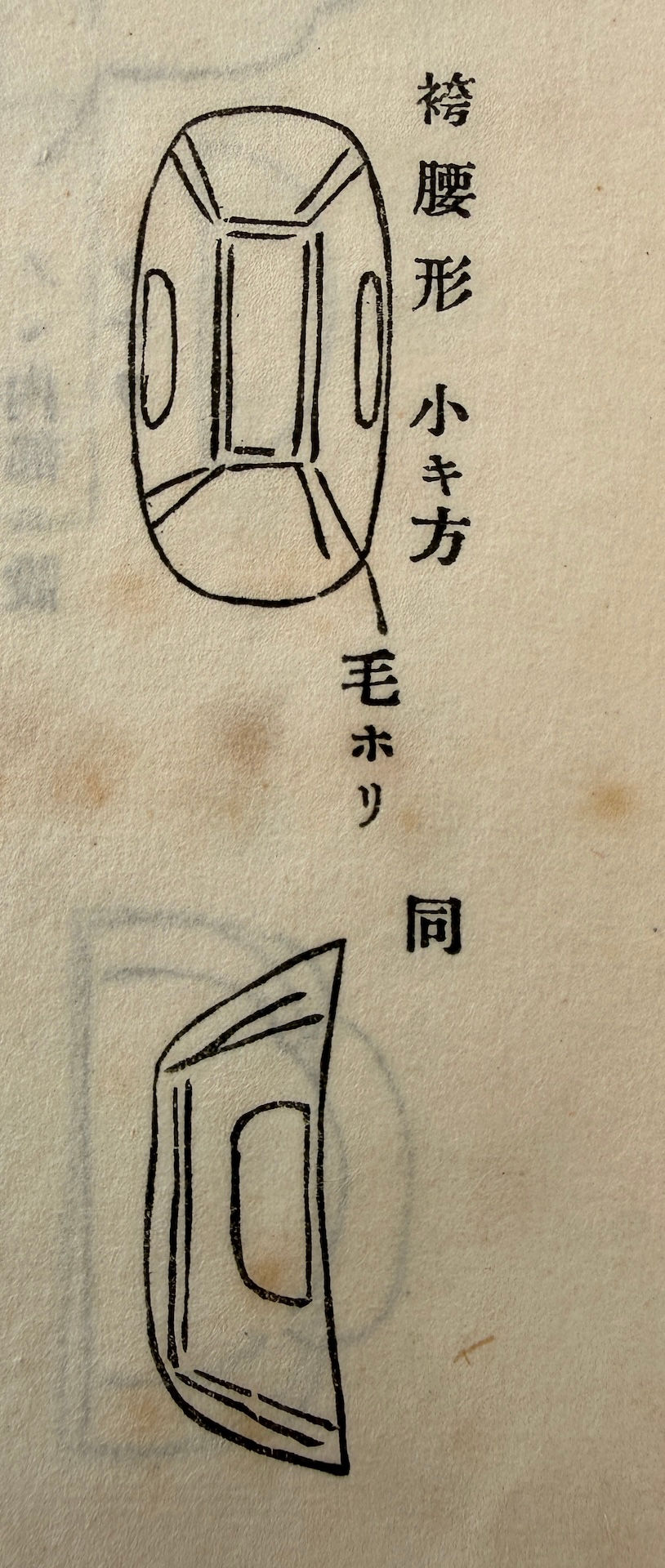

The entrance used by the host is known for its distinctive shape called hakama-goshi. Interestingly, a form known as hakama-goshi also exists in Higo-style kashira, as introduced in the Higo Kinkō-roku.。

The Aesthetics of Rikyū

At Muichian, part of the yōji-bashira (toothpick pillar) is intentionally concealed behind a wall. In Higo tsuba, one sometimes finds works in which patterns are carved into the mimi (rim) and then partially filled with keshikomi zōgan (flush inlay)—yet not completely. Areas are deliberately left uninlaid.

This approach resonates precisely with Rikyū’s aesthetic sensibility, which finds beauty in wabi—imperfection and incompletion—and offers a compelling parallel between tea aesthetics and Higo metalwork. For me, this provided a sense of quiet clarity and conviction.

According to the “Hosokawa Godai Nenpu”, Hosokawa Sansai once showed Rikyū a samegawa scabbard he had purchased at a small shop on Teramachi street in Kyoto, seeking advice on how to create a refined mounting. The result was the so-called Nobunaga goshirae. Despite the forty-year age difference between them, Sansai—himself a warrior and the son of Hosokawa Yūsai, who transmitted the Kokin-denju—possessed a deep cultural and artistic education that enabled him to understand Rikyū’s wabi aesthetics.

Rikyū himself commissioned Hon’ami Kōtoku to create a lacquered aikuchi goshirae for a tanto, Kobuya Tōshirō. The piece features a jet-black scabbard adorned with refined shakudō plum-branch menuki—an understated yet powerful expression of taste.

The families who gave tangible form to Rikyū’s aesthetics through the creation of utensils are known as the Senke Jisshoku (Ten craft professions servings the House of Sen). Among them, the Komazawa family, specialists in woodworking, produced sword racks favored by Rikyū.

My father’s book, “Katanagake”, published in 2023, this kiri itomaki katanagake is introduced. This type of freestanding sword rack appears even in a portray of Uesugi Kenshin, suggesting an early origin. Its placement near the nijiriguchi in tea rooms helps explain its function.

Regarding this piece, the book notes that it bears the seal of Komazawa Risai, and that the outer box is inscribed “Gensō gonomi”, indicating it was favored by Kakukakusai (1678-1730), the sixth-generation head of Omotesenke who served the eighth shogun Tokugawa Yoshimune. However, it is also said that Rikyū devised this form and had it made.

Closing thoughts

The origins of Sen no Rikyū’s aesthetics lie in Sakai, where he spent most of his life. His spirit of wabi-cha—finding clarity, purity, and inner richness within simplicity and imperfection—left a profound mark on tosogu. Zen and the Way of Tea were essential elements of samurai education and played a central role in shaping the cultural and artistic currents of their time.

In the next article, we will explore “What is Nobunaga goshirae?” Until then, stay tosogu & sword minded ♡

References:

Higo Kinkō-roku — Shigenao Nagaya

Ryūkōzan Nanshū-ji Temple — Official Temple Pamphlet

Sakai Rishō no Mori

Kobori Enshū School of Tea Ceremony

Omotesenke — Rikyū in His Youth

Kansai–Osaka 21st Century Association

Kitano Tenmangū Shrine — Kitano Tenmangū and the Plum Tree

Let us inbox you Samurai Newsletters! SIGN UP HERE!

Comments