Nobunaga Koshirae — Born from the Aesthetic Vision of Sansai and Rikyū

- gallery陽々youyou

- Feb 13

- 6 min read

Updated: Feb 14

The spirit of cha-zen ichimi—the unity of Tea and Zen—matured into the aesthetics of wabi-cha, becoming emblematic of the cultural spirit of its time. Among those who understood Sen no Rikyū’s sensibility most deeply was Hosokawa Sansai, counted among Rikyū’s Seven Disciples. The son of Hosokawa Yūsai, who inherited and transmitted the classical poetic tradition of Kokin-denju (a hereditary system of court poetry learning). Sansai was raised in an environment rich in literature and the arts. He is known to have possessed a refined cultural and artistic sensibility from an early age. Above all, he appears to have cherished his deep bond with Rikyū more than anyone else. This article examines the Nobunaga koshirae (goshirae), which was shaped by the shared aesthetic vision of Sansai and Rikyū.

A Koshirae Born of Two Aesthetic Minds

Although the correct Japanese pronunciation would be Higo goshirae, Nobunaga goshirae, or Kasen goshirae, for clarity this article will use the term “Nobunaga koshirae.”

Among the prototypes that later influenced the development of Higo koshirae are two types of koshirae devised by Sansai and produced in Kyoto during the Tenshō period: the Kasen koshirae and the Nobunaga koshirae.

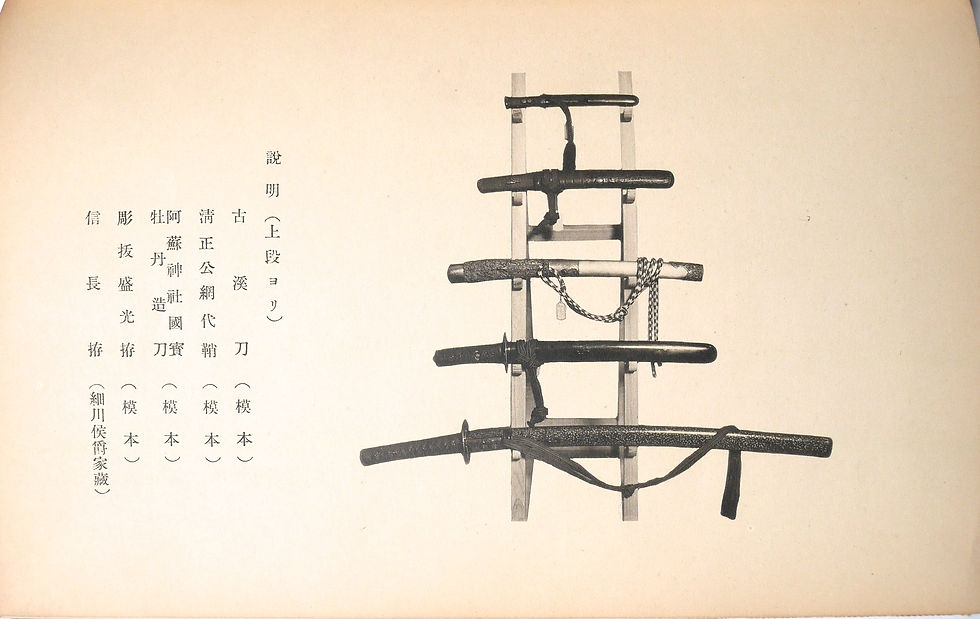

The Kasen koshirae survives today in the collection of the Eisei Bunko Museum. The Nobunaga koshirae, however, disappeared after the war. The only surviving photograph appears in “Higo Tōsōroku”, published on March 18th, Showa 9 (1934) by Kataoka Sosen. There, under the heading “The Beloved Sword of Lord Hosokawa Sansai,” the circumstances surrounding its creation are recorded in detail.

When I read it alongside Murakami Kōsuke’s “Chronicles of Five Generations of the Hosokawa and Their Swords”, I began to sense the exchange between Sansai and Rikyū—two men of cultivated taste refining a koshirae through careful deliberation. To imagine the words and smiles they may have shared fills me with delight.

Despite its name, the Nobunaga koshirae has no direct connection to Oda Nobunaga. The designation comes from the sword for which the koshirae was originally made—a work by Nobunaga, a swordsmith of the Asako Taima lineage active in Kaga Province during the mid-Muromachi period.

According to “Chronicles of Five Generation of the Hosokawa and Their Swords”, the preparation of the Nobunaga koshirae proceeded as follows.

Polishing was entrusted to Takeya, and the fittings were commissioned from Tamura. The lower habaki was made in silver so as not to appear overly austere. For the habaki itself, twenty examples of the same design were ordered to make. From these, I (Sansai) selected a single piece and had the remaining nineteen discarded.

Fuchi of the tsuka had been preserved wrapped in imported leather. Over time, areas of wear appeared and were carefully repaired. The ray skin for the tsuka had originally been purchased for the price of one gold koban (coin), a considerable sum. When mounted, it became the subject of remark, with people saying that “though he was but the lord of a small province, he appeared almost excessively splendid. The large nodules of the ray skin were noted for their regularity, evoking the Kuyō mon. It came to be known as the “Nine-Star Ray Skin of the Lord of Etchū.”

The menuki and kogai were carved by Yūjō with octopus motifs. The tsuba was a bold iron sukashi with inlay along the mimi; within the Hosokawa family, tsuba of similar characters were referred to as “Nobunaga-sukashi.” The scabbard was likewise refined through repeated consideration, careful attention and laterally putting heart into it.

When Sansai presented the completed koshirae to Rikyū, he praised it, remarking that from the standpoint of cultivated taste, the combination was harmonious and without fault.

Rikyū then added that he himself had acquired a similar scabbard and had kept it at hand. When the two were compared, they proved remarkably alike—down to the placement of the kurikata, the kaerizuno, and the shaping of the scabbard. Rikyū had discovered his example hanging in a small shop along Teramachi street in Kyoto, recognizing it as an exceptional old scabbard, so he purchased it.

From this episode, it is written that Sansai felt that Rikyū’s sense of beauty was remarkable in every respect; Rikyū, in turn, felt the same, and the two praised one another.

I stated in the previous blog that “Hosokawa Sansai once showed Rikyū a samegawa scabbard he had purchased at a small shop on Teramachi street in Kyoto”. That was incorrect. It was Rikyū who found and acquired the scabbard there.

Where, then, did Sansai obtain his? Further reading of “Chronicles of Five Generations of the Hosokawa and Their Swords” reveals that Tadaoki (Sansai) maintained a longstanding interest in koshirae. Murakami stated that in the “Hon’ami Gyōjōki”, it is recorded that a scabbard purchased in town by Hon’ami Kōtoku was later requested by Sansai and transferred to him. This scabbard may have become the foundation for the Nobunaga Koshirae.

Moreover, It becomes clear that Hon’ami Kōtoku received commissions from figures of influence and cultural standing, such as Rikyū and Sansai, and was entrusted with the mounting of their swords. At the time, Rikyū was still living, and the aesthetics of wabi-cha shaped the cultural climate. Kōtoku’s cousin, Hon’ami Kōetsu who is 4yr younger than Kōtoku, was also active. Sansai was the youngest; Kōetsu was five years his senior, and Kōtoku nine. It is easy to imagine what a richly cultivated age it was, with such men of refined taste all active at once.

The Only Surviving Full-Scale Design Drawing

“Higo Tōsōroku” also records detailed descriptions of the fittings used in the Nobunaga koshirae. These derive from a private viewing held in mid-October Shōwa 6 (1931), organized by the Higo Tōkenkai at the Kumamoto Kangyōkan, where the koshirae was exhibited. The full-scale design drawing of the Nobunaga koshirae was also executed at this occasion.

Nobunaga koshirae sword

Mei: Nobunaga (Kashū jū).

Era: the Ōei period.

Measurements: 2 shaku 0 sun 8 bu (approximately 63cm).

Kashira was carved in shibuichi with waves in kebori and yamamichi (a mountain-ridge motif) in deep curving. Fuchi in higoshi shape was wrapped in azuki (red beans)-colored leather. Tsuba was an iron Ko-Shōami namako-sukashi with silver thunder-pattern inlay on its rim. The menuki and kogai depicted octopus motifs in shakudō. For the kozuka, after careful deliberation and consultation with Rikyū, a plain silver which had was marubari (rounded form) was selected. The tsuka was wrapped in smoke-treated leather. The scabbard was finished in black lacquer over fine ray skin. The kojiri was in iron with a subdued finish called dorozuri, and the sageo was in hōkyō-cha color, woven in uneuchi (ribbed braid).

Its refinement was described as arising from the profound spirit of tea. In later times, koshirae modeled on this example extended beyond Higo, reaching as far as Edo.

The surviving design scroll is an invaluable document. Unrolled, it records the precise dimensions of each component used in Sansai’s Nobunaga koshirae. This material is intended for inclusion in Mitsuru Ito’s forthcoming volume “Higo Koshirae”, scheduled for publication in 2027, which will present full-scale drawings of the Nobunaga koshirae together with the Kishuso koshirae and the Horinuki Morimitsu koshirae.

This uchigatana koshirae represents a Nobunaga-style koshirae produced in Higo during the early Edo period. It is said that successive heads of the Hosokawa family commissioned reproductions of both the Nobunaga koshirae and the Kasen koshirae.

Closing Thoughts

Sansai understood more deeply than any of Rikyū’s other disciples that within simplicity—even within incompleteness—there resides a clarity and inner richness at the heart of wabi-cha. That Rikyū himself had discovered a nearly identical scabbard along Teramachi street suggests not coincidence, but a shared refinement of taste. The Nobunaga koshirae was born from the meeting of these two cultivated minds. I can only hope that, someday, Nobunaga koshirae may once again come to light.

In the next blog, we will explore “What’s the origin of Hachi no ki motif tsuba?”. Until then, stay tosogu & sword minded♡

References:

Higo Tōsōroku (肥後刀装録) March 18th, Showa 9 (1934)— Kataoka Sosen

Chronicles of Five Generations of the Hosokawa and Their Swords (細川五代年譜と刀剣)— Murakami Kōsuke

Let us inbox you Samurai Newsletters! SIGN UP HERE!

Thank you for sharing this information. Fantastic.