Marching Toward Sekigahara — The Spirit of the Samurai Encapsulated in Tosogu.

- gallery陽々youyou

- Dec 8, 2025

- 6 min read

Following our journeys to Hikone Castle and Chikubushima, we continue exploring historic sites deeply connected to sword fittings. In this chapter, Samurai Journey III: Sekigahara invites us to explore the ethos of samurai who lived through a turbulent age. By tracing the lives and alliances of influential daimyō, we reveal the elegance of samurai culture and the noble spirit expressed through tosogu.

The Battle of Sekigahara — Tokugawa Ieyasu’s Eastern Army and Ishida Mitsunari’s Western Army

Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who unified Japan and served as Kampaku, passed away in Keichō 3 (1598) at the age of 61. The administration of the Toyotomi regime was entrusted to the council of five elders —Tokugawa Ieyasu, Mōri Terumoto, Maeda Toshiie, Ukita Hideie, and Uesugi Kagekatsu—and Gobugyō (the five commissioners)—Asano Nagamasa, Ishida Mitsunari, Mashita Nagamori, Natsuka Masaie, and Maeda Gen’i. In Keichō 4 (1599), Maeda Toshiie, a key mediator between the factions, died, causing the regime to split into two opposing camps.

The famous poem recorded in Kasshi Yawa captures Tokugawa Ieyasu’s temperament perfectly:

“If the cuckoo will not sing, I shall wait until it does.”

Throughout the Toyotomi administration, Ieyasu remained composed, fully aware of his position, and strategically waited for the moment when Hideyoshi was no longer present. He excelled at reading the hearts and intentions of others, much like discerning the movement of shogi pieces on a board.

At the Gifu Sekigahara Battlefield Memorial Museum, the relationships between the commanders of the Eastern and Western armies are clearly illustrated, providing fascinating insight. The panoramic glass observatory offers a 360-degree view of the battlefield. The basin of Sekigahara—approximately 120–130m above sea level—allows one to imagine the battle formations of both armies and almost hear the warriors’ heartbeats. The museum also screens an animated film about the battle and provides maps for hiking and cycling routes around the camps and historic sites of the participating warlords.

Eastern Army

Tokugawa Ieyasu, Ii Naomasa, Honda Tadakatsu, Fukushima Masanori, Hosokawa Tadaoki, Tanaka Yoshimasa, Kuroda Nagamasa, Katō Kiyomasa, Tōdō Takatora, Date Masamune, Asano Yukinaga, and others—approximately 70,000 troops.

Western Army

Ishida Mitsunari, Mōri Terumoto, Ukita Hideie, Ōtani Yoshitsugu, Konishi Yukinaga, Shimazu Yoshihiro, Ankokuji Ekei, Shima Sakon, and others—approximately 80,000 troops.

Hideyoshi left a will stating, “Political marriages shall be prohibited.” Indeed, marriage was one of the most effective means of binding families as allies. In defiance of this instruction, Tokugawa Ieyasu strengthened his influence by arranging several politically motivated marriages, such as giving his adopted daughter, Manten-hime, to the adopted son of Fukushima Masanori.

This led me to wonder about another bond—religion. If two daimyō shared the same faith, it would be natural for them to regard one another as more than mere allies. And if they were Kirishitan (Christian) in that era, their connection would be even deeper.

Master Artisans of the Momoyama Period and Their Connection to the Daimyō

Why did Nobuie (hanare-mei and futoji-mei), one of the three greatest tsuba makers, produce so many works featuring Kirishitan motifs—roses, crosses, and related symbols? The rose motif carries a particularly intriguing meaning. In Nobuie by Mitsuru Ito, it is explained that:

“The rosary—composed of beads and a cross used for prayer—derives from the Latin word rosarium, meaning a ‘crown of roses.’”

Since Christianity was introduced to Japan around Tenbun 19 (1550), it is natural to think any works bearing Christian motifs must have been created after that time. Earlier researchers proposed several theories regarding where Nobuie worked. In the influential study “Nobuie no Shin-kenkyū (New research on Nobuie published in Tōken Bijutsu, 1958–1959) by Katsuya Shunichi, similarities between the works of Nobuie, Hōan, and Yamakichi are highlighted. As there were churches and missionary residences in Kiyosu, the study suggests that Nobuie may have lived and worked there.

Drawing from Ito’s book Nobuie, it clarifies that both Hōan and Yamakichi had origins in Kiyosu, which helps us understand their relationships with the daimyō of the region:

· A third-generation Yamakichi tsuba bears the inscription “Resident of Bishū (Owari).”

· Historical texts called “Geihantsūshi” note that Kawaguchi Saburōemon Hōan was born in Kiyosu and practiced metalwork. Later, he was summoned by the Asano clan and given a stipend while in Kai Province.

So what connection did daimyo sharing the same belief—Tanaka Yoshimasa, Fukushima Masanori, and Asano Yukinaga—have with Kiyosu?

Tanaka Yoshimasa, who received the baptismal name Bartholomeo, was a key retainer of Toyotomi Hidetsugu and governed Kiyosu Castle on Hidetsugu’s behalf. From 1590 until the Battle of Sekigahara, he simultaneously ruled Mikawa Okazaki, giving him tremendous influence in both areas. This explains why both Nobuie signatures—the hanare-mei and the futoji-mei—feature Kirishitan motifs.

Fukushima Masanori, a warrior of the military-oriented faction, came to govern Kiyosu after Hidetsugu’s death in 1595. He protected the Christians under his rule, and after distinguishing himself at Sekigahara, he became the daimyō of Hiroshima with 500,000 goku, relocating in 1601.

Asano Yoshinaga was also a Kirishitan daimyō. Although he did not join the main battlefield at Sekigahara, he was considered part of the military-oriented faction. His relationship with Masanori deepened—beyond political alliance—as they even served together as imperial guards in Kyoto after the battle of Sekigahara. Yoshinaga later relocated from Kai province to Kii province.

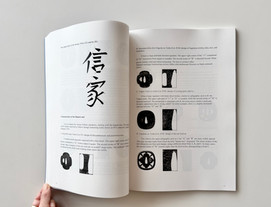

Let's take a closer look at works by Hōan and Nobuie

Yūgao-trellis motif tsuba, design of evening glory trellis

The first-generation Hōan

This piece is nagamaru-gata (oval form) with kaku-mimi koniku (between square and round rim). The seppadai rises gently into the center. The well-forged ground shows rich iron texture. The design sections were created by applying lacquer and using the kusarakashi technique (acid etching). A light yakite finish softens the sharp edges, creating a warm, dynamic surface. This method—combining acid etching and heat treatment, Yakite—is characteristic of Hōan and can also be seen in works bearing the hanare-mei Nobuie signature. Hōan began his career in Kiyosu and later served the Asano family, moving to Kii after Sekigahara. According to Okamoto Yasukazu’s “Owari to Mikawa no Tsubako”, the first-generation Hōan passed away on May, Keichō 18 (1613) in Wakayama. He also stated the record of Hōan lineage.

Sangi sukashi tsuba, design of counting rods

Futoji-mei Nobuie

This tsuba has a slightly indented mokkō-gata shape. Its rim features a kaku-mimi koniku (midway between kaku-mimi and maru-mimi), from which the plate tapers toward the seppadai. The surface is finished with tsuchime, then sukashi was applied, followed by yakite, and finally a radiating Amida-yasuri was added. The sukashi design appears to represent sangi (counting rods) and a base. Since the Amida-yasuri pattern avoids these sukashi designs, it is evident that these are part of the original design. The interplay of tekkotsu, tsuchime, and yakite creates rich hiraji (surface). Futoji-mei Nobuie tsuba without uchikaeshi-mimi* are rare, making this piece particularly notable. It is large without hitsu-ana, exhibits excellent iron quality, and is in flawless condition—an outstanding work of futoji-mei Nobuie.

Futoji-mei Nobuie’s mei have some variations such as “San Nobuie,” “Sanshū Nobuie,” “Geishūju Nobuie,” and “Geishūju Fujiwara Nobuie.” The discovery of Sanshū-Nobuie clarified that San-Nobuie refers to Mikawa, as described in Nobuie by Ito. The transition from Kiyosu to Okazaki and later to Hiroshima is reflected in these regional signatures, helping us piece together which daimyō may have supported him.

Petit Kantei Points♡

Hōan

The first-generation Hōan likely honed his individuality while working alongside Nobuie and Yamakichi in Owari. His hallmark is the combined use of kusarakashi and yakite, along with the frequent placement of signatures on the back—quite different from Nobuie and Yamakichi.

Nobuie

Before studying the signature, start with the workmanship. All artisans were influenced by the cultural trends of their time. Both hanare-mei and futoji-mei Nobuie works feature Kirishitan motifs. According to Nobuie (pp. 40–45), bold-style signatures include “San-Nobuie,” “Sanshū-Nobuie,” “Geishūju Nobuie,” and “Geishūju Fujiwara Nobuie.” Their chronological and stylistic relations are examined in detail. Signature transitions are discussed on pp. 45–47. For comparison with actual examples, refer back to pp. 35–38.(For a full understanding of the research, reading from the beginning is recommended—but for today, let us focus on a “petit kantei” moment ♡)

For Readers Who Have Not Yet Obtained the New Book, Nobuie

Set against the dramatic cultural and political shifts between the Momoyama and early Edo periods—seen even in the events of Sekigahara—this publication presents new perspectives on Nobuie by analyzing both hanare-mei and futoji-mei styles, their transitions, and the underlying aesthetics. It also includes numerous practical kantei points.

Title: NOBUIE・信家

Author: Mitsuru Ito

Publisher: gallery youyou

Release Date: October 1, 2025

Price: ¥27,500 → ¥ 26,000 (until Dec 31, 2025)

English Translation & Commentary: ¥17,500 → ¥ 15,000 (until Dec 31, 2025)

Closing thoughts

The Battle of Sekigahara reveals how dramatically the lives and relationships of various warriors transformed in this turbulent period. From this vast history, we explored just a small portion of the samurai spirit reflected in the works of Nobuie and Hōan. Our next blog will feature “Lecture by Ito Mitsuru: What Defines Higo Kinko?” presented at the Naniwa Kodogu Kai. Until then, stay tosogu & sword minded : )

References:

Osaka Museum of History

Tokugawa Ieyasu, Sekigahara from historical references of the Shogun family

National Archives of Japan

Owari to Mikawa no Tsubakō, Okamoto Yasukazu

Nobuie, Mitsuru ItoJunior

High School History Textbook (Kyoiku Shuppan)

Let us inbox you a Samurai culture into your mail box. SIGN UP

Wonderful post, Rei-san. Beautiful photography, and very informative. Such fascinating connections. Thanks so much. 🙂